When the Town of Homestead incorporated on January 27, 1913, its officials had no municipal building in which to meet. Sistrunk Hall, a wooden building located just west of the 1911 Bank of Homestead building, became the first structure to be used for municipal purposes. The Hall was built by Edward A. Sistrunk, who owned the Homestead Grocery (later the home to Fuchs Bakery and now the home of Ages Ago Antiques) and who became Chief of Police for the town of Homestead in 1916. Sistrunk Hall burned down on September 7, 1916.

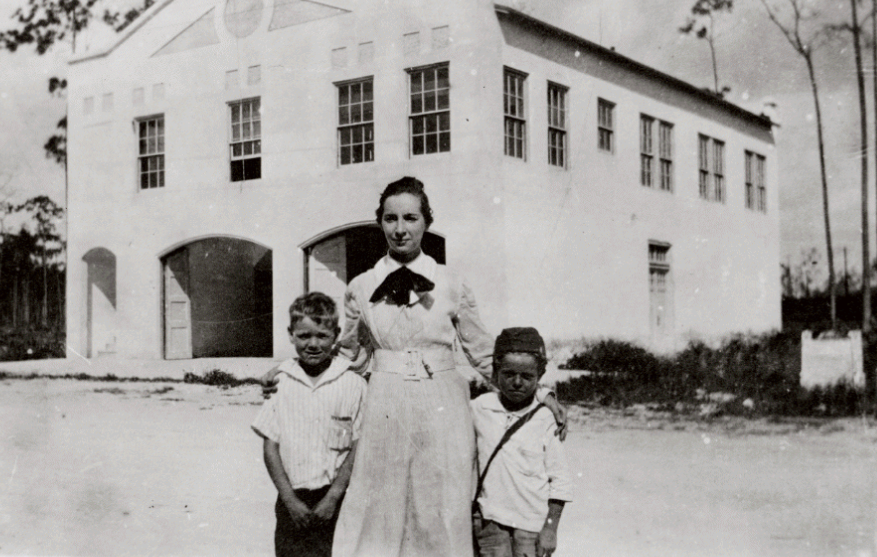

Recognizing the need for a town-owned municipal building, the Town Council considered several options. According to an article that appeared in the February 8, 1917, issue of The Homestead Enterprise, William J. Krome proposed a location north of Mowry, while G. W. Hall recommended a site south of Mowry. By a vote of 4-3, the Town Council decided to build the structure on lots 7 and 8 of Block 1 in the Commerce Addition. The lots cost $700, $300 of which was contributed by unnamed private individuals. At the same meeting, the town awarded the contract to build the town hall to John F. Umphrey for $4,418.00, exclusive of doors. He was to start work in 15 days and complete the job in 90. Umphrey, a local contractor, built a number of buildings in the area including what is now Neva King Cooper School. Two of Umphrey’s most well-known buildings are no longer extant. The Lodge in Royal Palm State Park, moved to Homestead in the late 1950s, was demolished after Hurricane Andrew and Homestead High School was torn down in 1983.

Harold Hastings Mundy, who was born in 1878 in Ontario, Canada, crafted the design for the structure. Mundy, an architect for the Dade County School district, also designed Coconut Grove Elementary School, Robert E. Lee Junior High School, and Miami Edison High School.

According to an article that appeared in the August 16, 1917 issue of The Homestead Enterprise, by August work on the Town Hall building had nearly been completed. The lower floor near the front of the building soon housed fire trucks and a hose-drying room, while the area at the rear of the building contained four jail cells for men. The jail cells for female prisoners were in a separate building located in back of the Town Hall. Municipal offices and a meeting room occupied the second floor.

In 1956, the Town Hall was remodeled after two city departments moved to other locations. The police department moved to its new quarters just east of the municipal power plant. That building now houses the Homestead Utilities offices. The fire department moved to its new building on N.W. 2nd Street. between N.W. 3rd and 4th Avenues. The jail cells were removed and the bottom floor was turned into office space for the growing city government.

The first Town Hall served the needs of the residents of Homestead for almost 60 years. In 1975, a new city hall, which had been in the planning stages since 1964, was built at 790 N. Homestead Boulevard. Edward M. Ghezzi, a well-known Miami architect who had moved to Homestead and occupied an office in the 1922 Redd Building, was awarded the contract in November of 1973 to design the new city hall. Ghezzi also designed the Shark Valley Observation Tower at Everglades National Park. The official dedication for the new city hall took place on November 23, 1975.

After the city vacated the old Town Hall, the building was used as a Senior Citizens Center and a State of Florida Department of Corrections, Bureau of Probation and Parole, office. In 1980, at the behest of local merchants seeking to increase parking along Krome Avenue, the City of Homestead resolved to demolish the structure. This decision triggered a fervent response from city residents. In a 5-2 vote on January 4, 1980, City Council members Nick Sincore, Bill Dickinson, Bill McConnell, Walter Rutzke and Tommy Wilson favored demolishing the building, while Irving Peskoe and Ruth Campbell opposed the measure. Those in favor asserted that the senior citizen center would be moved to a new building to be constructed in Musselwhite Park at the cost of $60,000. The historic value of the structure was not considered. Efforts by the opposition movement, led by Peskoe and Campbell, resulted in the donation of approximately $61,000 from members of the community and a State grant of $173,363 for the restoration of the building. Those community members who donated more than $250 are honored on an “Above and Beyond the Call” plaque mounted on the wall on the left side of the entrance to the Museum. On the wall just beyond the entrance to the building, bricks inscribed with contributor names honor those who contributed up to $250 towards the project.

Completed in late 1994, John Robert Barnes served as the architect of record for the restoration project. The Town Hall Museum opened in the structure shortly thereafter.

George Santayana is often quoted as having written that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The community of Homestead and the many people who visit our city can be grateful to the men and women who have recognized the importance of our historical structures and the documents and objects that illustrate our unique history and who have fought to preserve these resources for future generations.